Andy Hurrell recounts more memories of his days working as a Ghillie and considers the various benefits of using Ponies and Argocats.

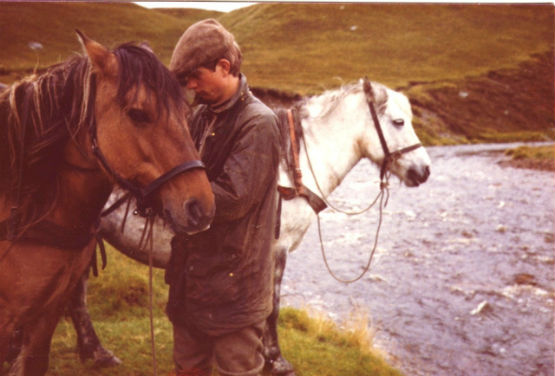

(Above: Fly, Andy Hurrell and Mayfly at Braeroy in 1980)

Until relatively recently, the entire infrastructural evolution of every industrialised nation in the world depended largely on the use of horses for transporting both persons and goods, so it's perhaps surprising that there isn't more day-to-day evidence or acknowledgement of the huge historical debt we owe our equine friends. Imagine how many horses put their backs into the building of St Paul's Cathedral, our canal and railway networks, the dark Satanic mills of the north or the ships of the Georgian navy.

But in the highlands of Scotland, hundreds of horses are still used to bring the annual harvest of red deer down from the hill to the larder. Back in the day, when Victoria and Albert were forging the modern-day Scottish deer stalking prototype at Crucible Balmoral, the utilisation of locally available highland ponies would have been a no-brainer: whether the continuance of this practice into the twenty-first century is solely for utilitarian reasons is a moot point. Most of the revenue derived by a landowner from stag stalking is fees paid by the guests: are ponies used to carry the stags because that's what the customers want, or are ponies still used because they do a better job than any available alternative? Are there sentimental and environmental considerations? Is it tradition maintained for tradition's sake?

The acid test, it might be argued, is whether there are any professional stalkers left in Scotland who, when working alone (that is, stalking without clients, as they often do during the hind season) favour the use of ponies. The veteran Scottish stalker Lea MacNally, in his classic 1968 publication 'Highland Deer Forest', says'that two hinds make a load for one pony', but that was written nearly half a century ago . . .

In the 1970s, at Braeroy, an estate bordering Lea MacNally's formative patch at Culachy, we used a Landrover to move ourselves and our equipment along the glen road, but we used ponies for carrying the stags off the hill, down to the roadside. Two of our six ponies had been backed well enough to be reliably ridable, so they also took turns, first thing in the morning, at carrying the ponyman to a predetermined rendezvous at the far end of the glen road: the stalker and guests set off much later, catching up in the Landrover. You'd have to be desperately tired, or suffering from a serious leg injury or perhaps just trying to dodge a soaking in a deep burn to prefer a ride on a pack saddle to shanks' pony. A pack saddle offers no more comfort than would an oversized barrel of malt whiskey (well, potentially rather less comfort than a full one). At Braeroy, happily, I rode out in the mornings on a horse fitted with a pukka riding saddle with stirrups, a bridle and a bit. Gordon Addison, the stalker at that time, stored the pack saddle in the Landrover and we swapped saddles after he'd caught up with me at the rendezvous.

We never used the ponies to carry stags along the road - what would have been the point when the Landrover was available? Once we'd got the ponies to the roadside, the stags and saddles came off and the burden was transferred to the Landrover and its trailer. Gordon was mindful not to make the ponies carry weight unnecessarily. Even unloaded, a leather deer saddle - just the saddle and the straps - is quite heavy: my guess is closer to three stone than two.

TV advertisements imply otherwise, but it seems to me that conventional four-wheeled vehicles, even with drive to each wheel, lose their efficacy in inverse proportion to the hardness of the driving surface. During my seasons at Braeroy, I recall that on both the two occasions we took the Landrover off the beaten track we very soon came unstuck. Well, by unstuck, off course, I actually mean stuck.

(Above: Argo and Crew, Sutherland 2013)

By contrast, the Canadian manufactured Argocat, an eight (or six) wheeled sit-in skid-steering All Terrain Vehicle, performs over the kind of soft ground that would leave any four-wheeled road vehicle floundering. It can, by a skilful operator, also be manouevred over lumpy terrain; uneven ground that would be completely no-go for any kind of mechanical transport short of a military tank. And, like a tank, an Argo can even be fitted with tracks, though it's default operational condition is eight or six small wheels, each shod with a wide floppy tyre.

But the Argocat has its limitations and most certainly can't be regarded as the off-road equivalent of The Great Panacea. It's definitely not a go-anywhere vehicle. Indeed, it has a number of Achilles' heels, the most serious of which is its potential to capsize - easily fulfilled if driven incautiously along the contour of even a modestly sloping hillside. In the 'Potential Hazards' section of the official Argocat manual it says 'side slope operation greatly increases the risk of rolling the vehicle over sideways'. To avoid this hazard it says, quite simply, 'do not drive your vehicle across the side of a hill'.

Last year, working in Sutherland, a young ghillie on a neighbouring beat gained first-hand experience of another of the Argocat's operational vulnerabilities. He nose-dived his eight-wheeler into a trench and grounded on the front of the bodywork. Traction in reverse gear proved elusive. His laudable efforts to use the ground anchor and electric winch to haul the machine out of its predicament precipitated a seriously pear-shaped turn for the worse: he forgot to keep the engine running while using the electric winch. The battery went flat. One of the most useless things in the world is a flat battery. A flat battery is especially useless when you're stuck on a hill in the Scottish highlands, five miles from anywhere with a pronounceable name, it's raining, you've got a fourteen stone lump of venison to get home and it's going to be pitch dark by eight o'clock.

Horses don't get flat batteries, but they have their own idiosyncratic and equally tiresome propensities, one of which is to sometimes fall over. On the last working day of the stag season, the horse my erstwhile flat-batteried colleague was riding lost its footing. He ended up in hospital (my colleague, that is, not the horse). And even to a ghillie on foot, a pony is a potential hazard. Leading a horse down a steep or slippery bank, for example, one should be aware of the possibility of inadvertently functioning as a soft landing mat for one's four-legged friend. Being rolled on by more than half a ton of live horse flesh, particularly if it has a sharp pair of antlers protruding from an additional load of freshly harvested venison strapped to its saddle, would almost certainly spoil one's day.

I've been lucky, so far, with horses, but as the author Ian Fleming observed, horses are dangerous at both ends. I was kicked last year by a colt, but half a second before he lashed out l'd been visited by a rare moment of clairvoyance and was thus able to sidestep the worst of the blow. I recall, however, with astonishing clarity, the two occasions at Braeroy when I had one of my feet trodden on by a fully grown highland pony. Of course, such an incident can only occur when one's working very close to a horse, when adjusting the saddle or loading a stag, for example. It's an eye-wateringly painful experience, which lasts as long as it takes for the animal to be persuaded to shift its weight elsewhere. I can personally testify, however, that though the actuality of the pain subsides within minutes of the horse removing its metal-shod hoof, the memory of it can linger for more than three decades. The health and safety wallahs insist that steel toecapped boots are the answer, but I shall refuse to accept that metal prophylactics can be comfortably incorporated into lightweight hill-walking boots until I hear that Himalayan sherpas are wearing them.

I was once helping Gordon Addison to shoe a horse in the yard at Braeroy when it trod on his foot (accidentally, one might assume, although this particular pony, Ginger, was a bit of a character). Gordon was holding a heavy hammer in his hand at the time. His two-fold response to Ginger's act of passive aggression was to utter an unrepeatably foul deprecation in a Scots Gaelic version of Anglo-Saxon, then to strike the beast a violent hammer blow to the forehead. Neither of these two retaliatory gestures appeared to cause Ginger the slightest offence. In fact, I caught Ginger's eye a moment before the hammer made contact. It seemed to me that despite his inscrutable, dead-pan, long-faced horse-like expression, Ginger was struggling to suppress a very naughty smirk . . .

To read the first part of Andy Hurrells memoirs click on the following link: pony-tales-memoirs-of-a-stalking-ghillie